A warning shot: One city in the Himalayas shows why climate change is a top priority at the G20

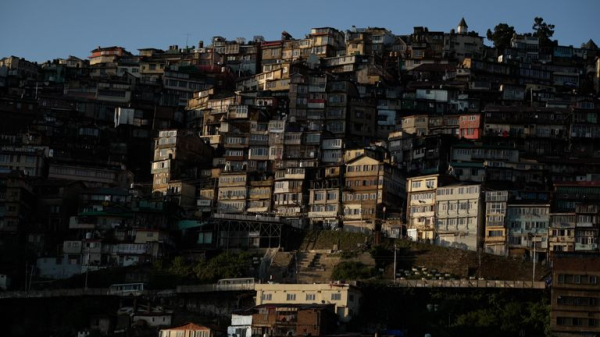

In the foothills of the Himalayas is Shimla – once the summer capital of the British Raj, known as the Queen of the Hills.

Shimla proudly sits 2,200m (7,200ft) in the mountains. But the Queen is crumbling – and she’s a warning shot to the rest of the planet.

It comes as India’s leader, Narendra Modi, kicks off G20 with climate change at the top of the agenda.

The prime minister recently called on countries to match his ambitions with action on climate finance and the transfer of technology.

Mr Modi has vowed to make India, the world’s fourth-biggest emitter of carbon dioxide, net-zero by 2070.

He is seen as serious about climate change, without compromising India’s economic potential.

But his country has some serious challenges to overcome.

That’s painfully apparent In Shimla and other parts of Himachal Pradesh in northern India.

Heavy rainfall and cloudbursts have swept rivers into towns, with roads and bridges washed away.

The torrent of extreme weather in Shimla wiped out an entire congregation.

Worshippers were praying at the Shiv temple in the early morning on 14 August when a landslide completely engulfed them.

It killed 20 people and wiped out three generations of one family.

I meet Jagdish Takur staring forlornly at the trail of destruction left behind.

He lost his nephew in the disaster, but it took 11 days to find his body under the mass of mud.

He’s just had his last rites read.

“Emotionally, it’s been very sad for us,” Jagdish tells me.

“The bodies were buried and thrown down into the valley. Nothing will replace them. One family lost seven people.”

It was rapid and brutal, but Parvati Thakur was one of the few who miraculously made it out.

She now hobbles up the steep steps of the hillside after injuring her foot.

“I heard a loud noise like lightning,” she tells me.

“I looked out and the whole roof had collapsed, and the temple was moving. We were so stunned, we didn’t even scream. I saw the temple being destroyed within a few seconds.”

This is not a simple story of Mother Nature though.

Environmentalist and former deputy mayor, Tikender Singh Panwar, says what’s happening in Shimla is “the planned destruction of the Himalayas”.

A few minutes’ drive through the winding roads, you can see the pain that progress has brought to these peaks.

Hotels and highways have cropped out at a rapid rate to accommodate tourists critical to the economy.

About 200,000 people live here, but it welcomes up to six million visitors every year.

The roads are packed – but critics say developments have been unregulated and unethical – many built with concrete that easily cracks, not the wood and local stone of old.

But there is no single culprit, and climate change has played a major role in the threat to this majestic and ecologically fragile place.

Monsoons are more erratic and unpredictable, and climate experts say reducing carbon dioxide is critical to minimising risk.

That’s a burden we all shoulder. Shimla is still captivating, but it has unique demands and qualities to consider. It needs saving and help from way beyond its own valleys.