How the Women’s World Cup final kiss row turned into Spain’s #MeToo moment

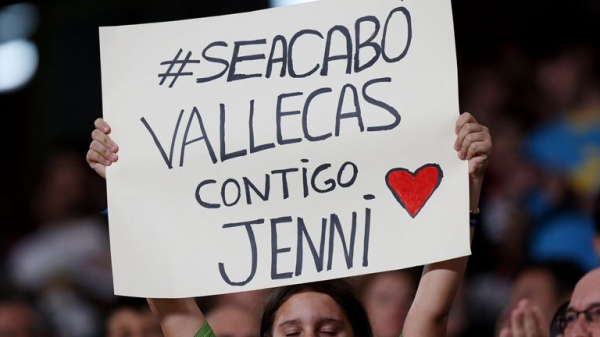

Ever since Spanish football federation boss Luis Rubiales grabbed player Jenni Hermoso and kissed her on the lips in response to the team’s World Cup victory, Spanish women have taken to the streets to say: “Se Acabo (it’s over).”

Mr Rubiales, who claims to be the subject of a “witch hunt”, has since been suspended by FIFA for 90 days and faces mounting pressure to resign.

Hermoso says she’s been the “victim of aggression” and in “no moment” did she consent to the kiss. Meanwhile, her team and coaching staff have refused to come back to work until Mr Rubiales is sacked.

Many are likening the growing solidarity movement to a Spanish version of #MeToo or #TimesUp.

Here Sky News takes a closer look at how the World Cup kiss has opened up the debate on women’s rights in Spain – and why it’s taken so long.

Issues with Spanish feminism date back to Franco

During the dictatorship of Francisco Franco, Spanish women’s status as second-class citizens was enshrined in law.

The civil code’s ‘permiso marital’ effectively made them the property of their husbands – unable to travel or have their own bank account without their permission.

It wasn’t until Franco’s death in 1975 two years before Luis Rubiales was born that this was revoked.

But even afterwards, years of brutal police crackdowns on any sort of group organising left Spanish feminism more on an individual level than a mass movement, says Dr Lorraine Ryan, assistant professor of Hispanic studies at the University of Birmingham.

So when other countries followed the US with its #MeToo movement after the Harvey Weinstein scandal broke in 2017, there was a noted lack of a “coherent” equivalent in Spain, she tells Sky News.

“Spanish feminism has always been diluted by the competing demands between older and younger feminists during the transition to democracy about what form it would take.

“So the feminism that predominates in Spain is neoliberal feminism, which is highly individualistic – and doesn’t allow for collective solidarity.”

This tension between young and old can be seen in the difference between the women marching in Madrid in solidarity with Hermoso and Mr Rubiales’ mother going on hunger strike in his defence, she adds.

Laws have changed – but some attitudes have not

Mindful of its record on women’s rights, under left-wing prime minister Pedro Sanchez, the Spanish state has invested heavily in gender reform.

“Spain has changed so much, particularly in the last decade,” Spanish journalist Maria Ramirez tells the Sky News Daily podcast.

“If you look at some measures like the UN ranking on gender equality, Spain fares better than the UK because we have more women in parliament, lower maternal mortality ratio and adolescent birthrate,” she says.

Spreaker This content is provided by Spreaker, which may be using cookies and other technologies. To show you this content, we need your permission to use cookies. You can use the buttons below to amend your preferences to enable Spreaker cookies or to allow those cookies just once. You can change your settings at any time via the Privacy Options. Unfortunately we have been unable to verify if you have consented to Spreaker cookies. To view this content you can use the button below to allow Spreaker cookies for this session only. Enable Cookies Allow Cookies Once

Click to subscribe to the Sky News Daily wherever you get your podcasts

In 2008 it set up a dedicated Ministry of Equality and earlier this year it gave female employees the legal right to three to five days “period leave” for menstrual pain.

2023 has also seen the culmination of a rape case that some say was Spain’s original ‘MeToo moment’.

After an 18-year-old student was gang raped by five men during Pamplona’s famous bull run in 2016 – in what became known as the ‘wolf pack’ case – a court acquitted them of rape on a technicality that meant because they didn’t use violence to coerce the victim, they were only guilty of the lesser offence of ‘sexual abuse’.

A protest movement emerged on the streets and online – and this year Spain finally passed its ‘only yes means yes’ legislation, which means both parties must verbally consent to sex.

But the outcry around the wolf pack case sparked a fierce backlash among some men, which was seized upon by the far-right and Santiago Apascal’s Vox Party.

“Spanish women no longer want the Spanish macho man of yesteryear, they’re no longer subservient to them – but there’s been a backlash to women’s progress,” Dr Ryan says.

This has manifested in a fresh wave of support for Mr Apascal’s “retrograde, nearly quasi-Francoist” take on women’s rights, she adds.

“For me, the Rubiales affair brings to light the asymmetry between token institutional reform and the everyday reality for Spanish women. It shows how embedded those attitudes still are.”

Dr Jane Lavery, associate professor in Latin American and Iberian studies at the University of Southampton, agrees.

“Despite the advances in Spain, sadly gender discrimination, sexual abuse and hypermasculine behaviours still prevail today, with men often abusing their positions of power – as we see in the Rubiales case,” she says.

This comes in the form of workplace inequality, harassment and domestic violence, which she says are still “endemic”.

And although Spain is one of the few EU countries to specifically track the killing of women and girls, eight women being killed by their current or ex-partners in eight weeks forced protesters to take to the streets earlier this year with placards saying: “Machismo kills”.

Why have women finally said #SeAcabo to Rubiales?

While the 2016 wolf pack case had elements of #MeToo, it didn’t have the same level of response the World Cup kiss row has had, journalist Maria Ramirez tells the Sky News Daily podcast.

The reasons for this are threefold, she says. Their international status has pushed the debate beyond Spain’s borders; female sports journalists have insisted on covering it – even when the players themselves were reluctant; and the reforms brought in since 2016 send a message that Spanish society has changed.

“Seven years ago there was #MeToo in Spain, but the laws nor many of those in power were there to support women,” according to Dr Lavery.

“But now women’s football has garnered much more attention, they’re paid more, they have celebrityhood on their side.

“Like with Weinstein in the US, it was celebrities coming out to talk that finally brought him to justice.”

Men have also come out in solidarity, with #SeAcabo appearing on the shirts of the Sevilla team last week and male politicians from Spain to the UN making statements, she adds.

In contrast, when 15 of the Spanish national team refused to play over claims coach Jorge Vilda wasn’t concerned about their “physical and mental health”, the football federation backed him – this time they’ve urged Mr Rubiales to step down.

Dr Ryan says the Rubiales affair showcases the new wave of Spanish women who “won’t accept their mothers’ lies”.

“It’s consolidated the unacceptability of men being entitled and saying: ‘I want to touch you’.”

But she warns that even if he is sacked or resigned – he could still be reinstated.

“We have to be careful in praising Spain for its gender reform. The ‘Macho Iberico’ is still alive and aided by institutional structures that might not be apparent to us but are very, very powerful. So will this crystalise gender reform? Or will he be reincorporated in six months to a year?”

Dr Lavery adds that systemic issues around gender will only be properly dealt with if education goes alongside political and legal change.